One of the most significant global trends in investing at all levels, from mum and dad investors to the largest institutional organisation such as major super funds and hedge funds is restricting the commitment of funds to companies that have passed an ESG filter test.

The shorthand term is ‘ethical investing’

Environmental, Social and Governance is defined by Investopedia thus:

Environmental criteria looks at how a company performs as a steward of the natural environment. Social criteria examines how a company manages relationships with its employees, suppliers, customers and the communities where it operates. Governance deals with a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits and internal controls, and shareholder rights.

Why is ESG investing on such a roll? There are two main drivers.

First is the logical reason that an increasing number of people worldwide don’t want to financially support companies whose activities they may disagree with, or at least do not actively support. For instance, gambling, weapons manufacturing, cigarettes and tobacco production and distribution, petroleum, coal mining and so on.

Second, is that there is a body of research promoted by various ethically investing organisation, such as the Responsible Investing Association of Australia (RIAA) that purport to show that investment returns are greater for ethically operating companies, that is, with an positive ESG rating.

But a word of caution: ESG is no ‘magic pudding’: it is absolutely possible for ethical funds to perform better, but if one is thinking of investing in ethical funds so that you can

There are 1,600 stocks in the MSCI World Index – a common investing benchmark containing only very large companies. If you give fund manager A the ability to invest in any stock and fund manager B the ability only to invest in 800 of the better ethical stocks, then you are asking fund manager B to beat fund manager A with one hand tied behind his back.

The good news? Reducing the opportunity set that a fund manager has doesn’t affect performance too much – especially if you are only cutting out a few sectors. There are plenty periods where fund manager B will outperform.

The bad news? If fund manager A and B have the same skill, you have to expect the ethical one, in the long run, to have a worse performance.

However, it can play out differently in the real world.

For example, over the last few years, the oil price fell from $100 + to less than $20 and stock prices of oil companies plummeted. Energy is generally negative in ethical screens and so managers who couldn’t invest in oil stocks (the ethical managers) outperformed those who could (everyone else).

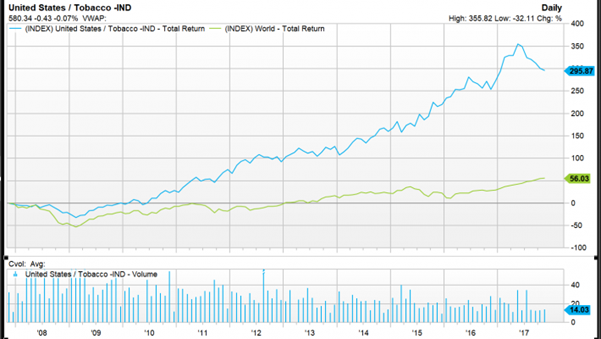

In the other direction, there are funds that exclude only tobacco, and these funds over the last 10 years have generally underperformed the world index as tobacco stocks rocketed up,” says Klassen. (Chart below)

You know it makes sense!

If there is a cause an investor is passionate about and wants to support companies in that area, there are four options, in order of the most helpful to least helpful:

- Make a donation. Are you trying to help or are you trying to make money? If it is the first then by donating you can feel good straight away, you get a tax deduction up front (rather than waiting to book a capital loss when you sell shares!). Donating directly to companies is not generally tax deductible – but if your cause is ethical then there likely will be industry bodies that are tax deductible.

- Buy the product yourself. Most companies want more customers rather than more shareholders – and the ones that don’t you shouldn’t be investing in.

- Buy shares from the company in a capital raising. That way your money will actually go to funding the company expand or its research and development.

- Buy shares on the market. This is the least helpful way of helping the company. All you have done is transferred money to another investor !