Grades, grades, grades. Explorers love to talk about them, the market is always eager to know about them, but understanding them can be like trying to learn a software coding language.

And then there’s the constantly changing goalposts on what “high grade” and “low grade” even means.

One company could call an assay result “high grade,” while another with the same result for the same mineral could call them “low” or “mid” grade.

This is especially true for gold.

But the goalposts can also change for lithium, iron ore, copper, nickel … and the list goes on.

And then there’s an unfortunate truth about the nature of investor-facing ASX communications. Those with ‘good’ grades say “grade is king.”

And those with ‘bad’ grades say otherwise.

To make things more confusing: based on the length of the drill core, the depth it was pulled from, the surrounding geology – and then, metallurgy – both parties can be equally correct.

So what are “good” grades, anyway?

Could you please be clearer?

I’ll try.

Before we get into defining what levels define a good grade and bad grade, let’s run through the basics of reading a drill result first.

You may be familiar with gold explorers, where you could see any of the following in an ASX announcement (the below are random examples I’ve imagined for the purposes of this explanation, using gold because it’s very common for the ASX.)

- 24m @ 4.2g/t gold from 19m depth (RCEXPL001), or

- 01m @ 85g/t gold from 180m depth (DDEXPL002), or

- 57m @ 3g/t gold from 13m depth (DDEXPL003), and so on.

Here’s a basic run-down on what to look out for, using the above three fabricated drill results as examples.

- Core length: The length of a drill result is the first number you see, measured in metres (m). This is most commonly referred to as “width,” given the act of laying them out on a horizontal table for assay. You may also see the term “thickness.”

In short: the longer the core section is, the better the reliability of a company claiming they’ve got a deposit worth mining. While the #2 result has impressive gold grades, it’s only a 1m section – basically useless for a real investment decision.

- Grades: We’ll dive more into grades shortly, but in the case of gold, you’ll typically see “g/t” used – this stands for “grams of gold per tonne.” Other metals use a % symbol to indicate concentration in a core sample, while other minerals will be measured in parts per million.

- Depth: In what can be the most overlooked aspect of all this by novice investors, in my view, depth is probably the most important thing to look out for.

A company can have a long core with high grades, but if it’s 300 metres underground (or 180m in the case of #2), you then need to ask a series of other questions: does the company have the money to mine that deep? Is there an existing open cut or underground mine from which to access these depths? Has the company ever mined that deep before?

Then there’s something else you should be looking out for, and this one’s a bit harder.

- Geology: This could be a whole different article on its own, and so I’m not going to get lost in the detail. Basically: greenstone-type rocks are ideal and quartz is always a good sign. You could see rare earths miners successfully finding REEs in clay but unless they can prove in metallurgy testwork they’re able to retrieve high grades, clay is something to be wary of.

A very common type of host rock you’ll see in ASX announcements is granite, and granite isn’t exactly ideal. It generally requires a lot of explosives, which is when one should also glance at financials again.

Okay. Can we talk about grades now?

Sure.

Not all drill results will use grams-per-tonne-of-ore (g/t).

That’s gold miner talk. You’ll also see g/t for palladium, platinum, and silver.

Many other grades will be expressed as a percentage (%).

You’ll see % for nickel, copper, lithium, cobalt, iron ore, and most other base metals.

Then you’ve got REEs and uranium, which are typically expressed as parts per million (ppm). Handy rule of thumb – 10,000ppm = 1%.

Luckily, UndervaluedEquity provides a quick cheat sheet on how to determine a drill result quickly and easily, though, these considerations must be made in regards to the points we discussed above: length, depth, and surrounding geology.

(A product of its time, that table also contains no grade information for lithium. As a rule, most lithium concentrations over 3% will reliably be called “high grade,” and this will be accepted by the market.)

It pays to remember that low grades are more viable at lower depths given they cost less to access; and the more low-grade shallow-lying ore you have, the better chances of making a commercial product.

At the same time, high grades within manageable depths are always going to catch market interest.

If an explorer can’t access those things themselves, should their acreage be good enough, many explorers may look to ‘get the ground ready’ for a larger player to move in as either a JV agreement (or like-for-like arrangement), and/or, a complete takeover or acquisition.

Real world examples

For the rest of the article, let’s go through a list of real-world companies listed on the ASX and go into less imaginary examples.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll be looking =t several minerals – some are and aren’t included on the above cheat sheet table from UndervaluedEquity.

Here’s what and who we’ll be looking at today:

- Lithium – Chariot Corporation (ASX:CC9)

- Gold – Barton Gold (ASX:BGD)

- Uranium – Infini Resources (ASX:I88)

- Vanadium – Vanadium Resources (ASX:VR8)

- Graphite – Triton Minerals (ASX:TON)

Note that this article is for information purposes only, and is intended to help one guide their research.

I make no claims to being able to give financial advice; nor am I a geologist. Food for thought.

And with that out of the way, let’s get started.

Lithium – Chariot Corporation (ASX:CC9)

Chariot Corporation’s (ASX:CC9) latest drill results, published on 2 February 2024, are a good example of how a shallow-lying orebody with grades on the low side can be of more value to an explorer than more psychologically desirable high grades buried deeper underground.

Remember when I said that lithium concentrations over 3% are generally considered high-grade?

Take a look at the following results Chariot posted:

- 15.48m @ 1.12% lithium (Li2O) from 2.74m depth (including a 4.27m section @ 2.46% Li2O slightly deeper at 9.94m depth.)

- 14.33m @ 0.84% Li2O from 1.83m depth (including a 2.29m section @ 3.09% Li2O from 10.67m depth.)

- 18.81m @ 0.85% Li2O from 45.26m depth (including 5.79m @ 1.08% Li2O from 47.55m depth.)

Macro headwinds in the lithium sector notwithstanding, Chariot believes shareholders are sleeping on its results.

The real kicker is that the company has a 15.5 metre long core section at 1.12% Li2O which starts at less than three metres from the surface.

Should the company’s future drilling further shore up confidence in the existence of a shallow-lying mineralised system large enough to warrant extracting, those shallow depths ultimately say one thing: low CapEx.

Gold – Barton Gold (ASX:BGD)

Gold results were for a long time the bread and butter of the ASX junior resources space, but lithium gave gold a run for its money.

But with gold prices reaching record highs in early March, this situation could be set to change.

The 2023 iteration of Diggers & Dealers saw lithium miners take away keystone awards long the exclusive right of gold miners.

Let’s take a look at recent results from Barton Gold (ASX:BGD).

In an exploration update published on Valentine’s Day, Barton Gold highlighted a series of earlier-completed diamond drill results which appear to indicate a gold deposit could be present.

Take a look at its results:

- 10m @ 4.08g/t gold from 109m depth

- 11m @ 6.24g/t gold from 80m depth

- 02m @ 35.05g/t gold from 68m depth

- 8m @ 2.16g/t gold from 112m depth (including an 8m section @ 5.99g/t gold from 132m depth)

- 16m @ 2.65g/t gold from 108m depth

Here we see an example of what I was talking about earlier – while Barton is posting some decent intersections of high-grade gold (at least as UndervaluedEquity sees it,) shareholders need to digest the depths these results were pulled from.

Diamond drills, able to run far deeper than aircore and RC drills, should be an early indication – the gold system, if large enough to warrant mining, is buried under 100m of earth.

Uranium – Infini Resources (ASX:I88)

Now we leave the world of percentages and grams-per-tonne to look at parts per million (ppm.)

This measurement is used for minerals which tend to occur underground in concentrations generally less dense than that for other metals where other types of measurements are used.

Typically, it will be for uranium or REEs (I’ve left rare earths out of this article because it could be its own.)

So what are high uranium grades? UndervaluedEquity posits concentrations over 0.40% and above are high grade.

In terms of ppm, that’s a read of over 4,000ppm. (As discussed: ppm is easy to figure out if you remember that 10,000ppm = 1%).

So let’s put that to task against Infini Resources’ (ASX:I88) latest published uranium results released to market on 29 January 2024.

The company flagged three mineralised rock samples:

- One sample at 865ppm uranium

- One sample at 836ppm uranium

- One sample at 385ppm uranium

In ppm terms, the first sample is thus 0.0865% uranium. Right off the bat, not really landing anywhere near the high-grade cutoff posted by UndervaluedEquity. There’s no way to spin that.

Infini’s shareholders will likely need to wait for hard-rock uranium drilling to commence before the market starts to salivate over what could be a significant Canada-based resource of the nuclear energy feedstock.

Vanadium – Vanadium Resources (ASX:VR8)

Now let’s turn to a more obscure mineral – vanadium. For this example, we’ll be looking at ASX-listed Vanadium Resources (ASX:VR8).

Historically a steel additive used to strengthen steel such that it can be manufactured to weigh less but retain integrity, the energy transition has also claimed vanadium in its jaws.

Vanadium can also be used in the manufacturing of Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries (VRFBs) – a competitor technology to lithium batteries in the big battery grid-scale energy storage space.

Currently China dominates the manufacture of VRFBs, and the rest of the world is watching – Australian companies included.

Vanadium pentoxide grades in hard-rock mining typically range around 1% but can extend up to over 2%, making a grade of 1.5% around the mark you’d start using the term “high grade.”

Based on the company’s Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) for its flagship South African vanadium project, the company bases its assumptions on the following grades.

- Pit 1 – 54M tonnes of ore at an average grade of 0.72% Vanadium (V2O5)

- Pit 2 – 26.23Mt of ore at an average grade of 0.69% V2O5

- Pit 3 – 2.83Mt of ore at an average grade of 0.73% V2O5

While we see the grades approaching the 1% mark, they don’t quite hit that psychological mark – but if the geotechs are right about how much ore the company has, that mightn’t be too bad a turn-off for investors.

Graphite – Triton Minerals (ASX:TON)

Finally, let’s turn to the forgotten battery metal – graphite.

The commodity triggered a flurry of activity on the ASX in October last year when China placed a ban on exports on graphite. However, this didn’t trigger quite the momentum investors probably hoped for.

Like uranium, a long-suffering cohort of graphite bulls have been ever waiting for the metal to reach similar prices to lithium.

Unfortunately, the world’s 2nd largest economy banning exports of the stuff coincided with a downturn in EV demand and collapsing lithium prices.

Graphite truly does have bad luck.

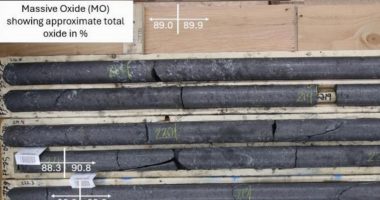

At any rate, concentrations are typically measured in “Total Graphitic Carbon” (TGC).

Graphite is interesting, because grades can vary from 3% TGC to up to more than 20% TGC. Typically, though, results top out around 5%.

Let’s take a look at Triton Minerals’ (ASX:TON) graphite project in Africa.

According to a DFS for the project, Triton Minerals stands in a position to boast high grades.

Looking at the company’s JORC, it assumes the following grades for its graphite ore across the following mineral resource estimate confidence levels.

- Probable – 6.20% Total Graphitic Carbon (TGC)

- Indicated – 6.90% TGC

- Inferred – 6.00% TGC

Given the notch above 5%, it’s safe to say that Triton Minerals could thus boast high graphite grades, if it wanted to. Information around depth was less well-advertised.

Takeaways & conclusions

Let’s do a speedrun for the main points in this article.

- Low grades and high grades differ for different minerals

- Investors should be keeping an eye on the length of reported intersections

- The depths those intersections come from are highly important to consider

- Geology (and metallurgical testwork) are also crucial to interpreting drilling results should that information be available

- Low-grade projects closer to surface can be more desirable than high-grade projects buried deep underground

- A handy rule of thumb for reading ppm results is remembering 10,000ppm = 1% hard-rock concentration equivalent.

-1200x645-380x200.jpg)