To look the part of Pamela Anderson in “Pam & Tommy,” the Hulu series, the actress Lily James sat through four hours of makeup each day and reportedly went through 50 pairs of 34DD prosthetic breasts, which had to be switched out repeatedly during filming and were at times so sweaty, they almost fell off.

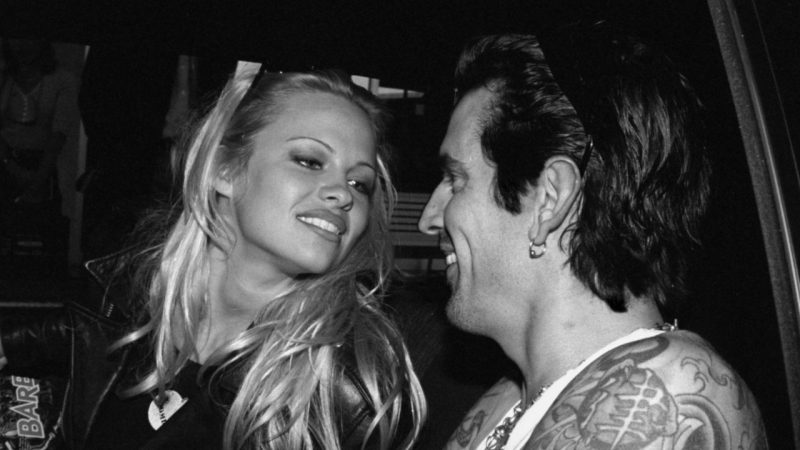

The series recounts the whirlwind marriage of Ms. Anderson and her ex, the Mötley Crüe drummer Tommy Lee, and centers on the honeymoon sex tape that was stolen from their home and distributed to the masses. But this retelling of their story, created without their involvement, purports to be the empowering version of events — an attempt to depict Ms. Anderson’s struggle in the aftermath and “provoke a conversation about how we treat women,” as Ms. James has put it.

So if the camera seems a little too interested in lingering on those prosthetic breasts? Don’t worry — this is feminist art.

And it’s the kind of art that seems to be everywhere in Hollywood these days, part of a slate of projects that aim to “reclaim,” “redeem,” “reframe” and “reconsider” famous, beautiful, usually white and always misunderstood women from our semirecent pasts, who were at one point vilified, usually over something sexual in nature. As the logic (and marketing language) tends to go, by retelling (and consuming!) these women’s hardships through the more enlightened lens of today, we are helping women reclaim their power.

“Pam & Tommy” is not the most recent example of this genre, though it is perhaps the most controversial — in part because Ms. Anderson wanted nothing to do with it. But by the time it was announced, in 2018, there was a whole host of other successful projects like it: a biopic and documentary about Anita Hill, recounting her treatment in her sexual harassment claim against Clarence Thomas; “I, Tonya,” about the figure skater Tonya Harding, now treated as more complex than just a low-class villain; and “Lorena,” about Lorena Bobbitt, who today goes by Lorena Gallo and who we now see was not merely the woman who chopped off her husband’s penis but also a victim of domestic abuse.

“They always just focused on it. …” Ms. Gallo said in 2019, in an interview published by The New York Times. “And it’s like they all missed or didn’t care why I did what I did.”

These stories played out before #MeToo, before social media, before we began reassessing everything from the art we consume to the monuments we’ve put up to the very date of our nation’s founding. And so, many of these recent attempts to look backward have been genuinely revealing: “Framing Britney Spears,” for instance, the Times-produced documentary from last year, and “Britney v. Spears,” the Netflix one, delved into the exploitative details of the pop star’s conservatorship, as well as the tabloid coverage of her, igniting a national conversation about conservatorship abuse. Documentaries on Janet Jackson, including one she produced, reignited conversations about her treatment in the aftermath of that infamous “wardrobe malfunction” at the 2004 Super Bowl, when her breast was exposed and she was blacklisted but the man who exposed it, Justin Timberlake, was not.

We owe some of this redemption framework to Monica Lewinsky, of course, whose affair with the president was the backdrop to my teen years and whose return to the public eye I arguably helped facilitate once I was old enough to recognise its complexity. I wrote about Ms. Lewinsky in 2015, shortly before she delivered a TED Talk on public humiliation, and then again last year, when she became the subject of the FX series “Impeachment.” (The show, which counted Ms. Lewinsky among its producers, tells the story of the affair through the lens of the women involved.)

Since then, I’ve applied a similar approach to the lives of other vilified women: Katie Hill, a former representative who resigned in a revenge porn scandal; Paula Broadwell, the onetime mistress (a word that has no male equivalent) of Gen. David Petraeus; Amanda Knox, who a decade ago was cleared of the sensational murder of her roommate but has struggled to find her footing since. These women were at times sympathetic characters and other times not, but plenty of nuance was left out of all their stories.

So I am not immune to the appeal of this redemption arc. And yet . . .

There is a term I learned recently: “scopophilia.” It means “the love of looking.” It could refer to pornography or even a car crash, but it is often used in film to describe the way we look at women who are portrayed onscreen. It is no secret that humans love consuming spectacle — and we doubly love a spectacle when it involves women and sex. But at what point does the fictional depiction of that spectacle, and our viewing of it, become just as bad as watching it in the first place?

Ursula Macfarlane, the director of an upcoming Netflix documentary about Anna Nicole Smith, the troubled actress and model who died of an accidental drug overdose at 39, said when the project was announced, “Now feels like the right time to re-examine the life of yet another beautiful young woman whose life has been picked over and ultimately destroyed by our culture.”

Perhaps — but at what point do such re-examinations merely perpetuate the tropes that made them worthy of applying hindsight in the first place? Who gets to tell such stories, who should profit from them, and when does all that talk about reframing and about upending the male gaze become more about the performance of redemption than about the woman at the centre?

The writer Kathryn VanArendonk has called this recent genre “empathy tourism”: an attempt to take viewers on a voyage to a past that’s recent enough to be recognisable but distant enough to feel bizarre. As a result, some efforts — and, perhaps even more so, the way that people talk about them — can tip into a kind of smugness.

We can still consume these stories, but through the lens of enlightenment. We get to feel good about where Ms. Lewinsky is today (she’s a producer!) but we still get to gawk at her flashing her thong to the president of the United States — a scene that, as she told me, she reluctantly signed on to.

We can nod along to heavy-handed dialogue — for example, “Sluts,” Ms. Anderson’s character declares after a disappointing court ruling, “don’t get to decide what happens to pictures of their body.” But we also get to do so while looking at her.

There’s nothing quite like rewatching a woman’s life collapse over a sex tape in the name of righting history.

For what it is worth, the real Ms. Anderson — who is having something of a renaissance at the moment — hasn’t seen the show about her. I’m told that she won’t. According to those close to her, she has few regrets in her life (not even Kid Rock), but that tape is the one thing she wishes she could undo. She is now at work on her own version of her story, a documentary with Netflix, co-produced by one of her sons, as well as a memoir.

Ms. Spears, now free from her conservatorship — the result, arguably, of the newfound attention stirred up by the films about her — has said she was “embarrassed” by “Framing Britney Spears” and is also working on a tell-all memoir.

Ms. Lewinsky has perhaps handled her rehabilitation the most delicately — by insisting on being a part of it. But even she has told me she would have preferred that the show about her didn’t exist at all.

“I hope it’s the last time,” she said.

There are enough tales of wronged women in history that we could keep telling these stories forever. But are we really any better off today for having heard so many of them?

It doesn’t take much effort to uncover examples of imperfect women whose lives are currently being picked over by our culture, in real time. Those whose credentials are questioned. Whose fashion choices are picked apart. Whose personal lives are violated by the tabloids. Whose downfalls, be they for good reasons or bad, are just a little too salivated over.

Last week the actress Amber Heard took the stand in a defamation trial against her. She is being sued by her ex-husband, Johnny Depp, over a 2018 opinion essay she wrote, in which she called herself a victim of domestic abuse. (Mr. Depp has denied abusing Ms. Heard and has accused her of abusing him.)

The outcome of the trial is still weeks away, and there are plenty of reasons to express skepticism about either side’s narrative. And yet it is Mr. Depp’s fans who flank the courthouse daily, waving from the galley, while social media — and the trial’s livestream — are inundated with anti-Heard memes and insults, calling her a “gold digger,” “fake,” “bipolar” and “manipulative,” to the extent that she has reportedly had to hire security.

Redemption plots are, in theory, supposed to teach us about empathy, about the inherent humanity of even messy, imperfect women. But what good are they if they can’t help shape the way we treat one another now?

Until the next redemption plot, I guess.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Jessica Bennett is a contributing editor of The New York Times’ Opinion section. She was appointed the paper’s first gender editor in 2017 as part of an initiative to expand coverage of women and gender issues. She teaches journalism at New York University and is the author of “Feminist Fight Club” and “This Is 18”.