Australia is the highest per capita spender on war memorials and paraphernalia on the planet. It builds interactive modern buildings in the middle of European fields like the $100 million Sir John Monash Centre in France, adding to the unchanged and controversial $500 million upgrade at the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra.

Some of this is due to the success of the AWM and its leadership under former Coalition leader and outgoing Chair Brendan Nelson, along with the likes of media mogul Kerry Stokes on the board. Under their almost two-decade tenure, the mythology of remembering war has evolved. From solemn remembrance to SAS: Australia. Now, for every forgotten soldier, we have a Channel 7 reality program, and another personal trainer or group of accountants walking the overwalked Kokoda track.

The re-framing of our military memory defines a more military-minded default from the governments who entertain it, hoping to form a broader acceptance from the population. Ben Brooker wrote in Overland in 2018 about the shifting perspective that this approach encourages: “We ought to be asking ourselves how a rejuvenated Anzac mythology . . . may influence our attitudes towards not just the wars of the past, but also the wars of the future.”

We see this in real time as veterans’ groups call for adequate funding, among a dangerous mental health epidemic affecting ex-servicepeople. Suicide rates among veterans are disproportionately high, partly due to an underfunded and ill-equipped sector that cannot provide adequate support, while the Australian Government is on track to spend $1.1 billion on war memorials between 2014 and 2028.

The first ANZAC Day football game between Collingwood and Essendon took place in 1995. Saverio Rocca and Paul Salmon traded goals end to end, a spectacle charged by the significance of something that couldn’t be understood. The teams drew and delivered one of the most incredible displays of modern Australian Rules football ever seen.

The meaning of the occasion sent electricity through the players, coaches, and spectators. It was on display on the pitch, alive in the stands, and demonstrated to a fledgling modern country — still searching for an identity in a post-war, post-white-Australia-policy landscape — the power of the solemn memory of war to enthral the national imagination.

There was something about having over ninety-thousand people in one place observing a minute’s silence that left a mark on the Australian population. The AFL, the RSL, and the Howard-era social engineers were looking to harness this military-inspired jingoism as fuel to power a poorly defined national identity. In the ANZAC games that followed, so too did a renewed interest in the plight of the ANZACs. Record attendances for dawn services followed year upon year, ever more powerful and solemn. They also helped to prepare a new generation of men and women for war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The memory of war had shaped the lives of diggers and their families, but it had also once shaped our foreign policy. After the Vietnam War in the seventies, with the Cold War skirmishes and the scarring of WWII so strong in the national psyche, Australia was less prepared to see things in terms of warfare and more inclined to enact effective regional diplomacy — less zero-sum-games and more aid programs and joint ventures.

It remained that way until the ANZAC Day games took centre stage in the early 2000s, just as the War on Terror had begun. Australia has since supported conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, while dropping from the top ten donors of global humanitarian aid and shifting instead to aspirations of becoming a top ten global arms manufacturer.

Out of the billions that flow into the memorials and the interactive light shows for the dead, fractions trickle to the living veterans that currently suffer after tours on the ambiguous battlefields of the War on Terror. For those screaming for funding to address societal crises and ensure the Department of Veterans’ Affairs is well equipped to adequately treat the crisis facing its veterans, another shiny marble monument or fancy isolated building in France could be insulting. It may seem that all of this is for a small cadre of bureaucratic lifers, swanning around Amiens and patting each other on the back, or for politicians to place a wreath at an overpriced monolith in Canberra. For everyone else, it hardly seems meaningful at all.

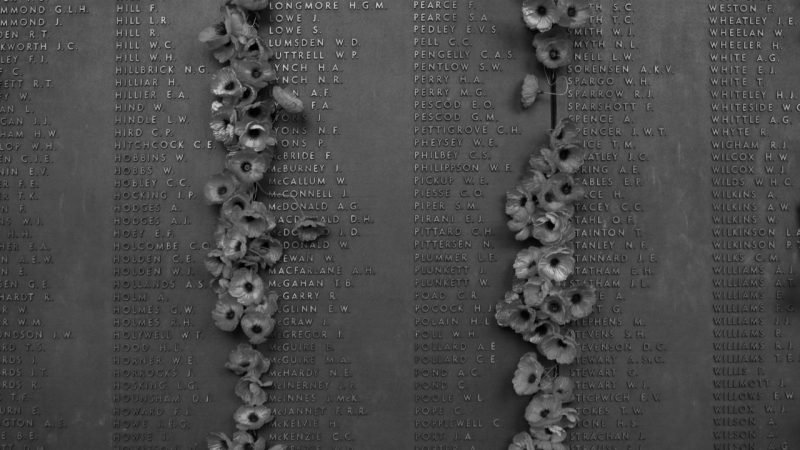

The disproportionate funding can be seen just on remembering of the Great War, without considering the other numerous wars that were not so great. David Stephens from Honest History calculated that Australia spends on average $8800 for each soldier killed (61,527 casualties) in WWI, compared with $109 for each British fatality and $2 for each German — both of which lost millions in the war. France, whose total military and civilian deaths number 1,737,800, also suffered the horrible destruction of WWI, but only spends $67 per soldier — substantially less than the cost of the monolithic Monash centre sitting in one of its fields.

As Kim Beasley replaces Dr Brendan Nelson as Chairman of the AWM, it is important to recognise the organisation’s transformative role in shaping the modern understanding of war, and to identify how it may be influencing our potential involvement in participating in it.

Beasley shares links to the arms industry like his predecessor Nelson, who acted inappropriately by lobbying funding from the weapons manufacturers as AWM Chair. According to War Memorial historian Professor Peter Stanley from UNSW Canberra, this compromise has changed the entity “for the worse — forever”. Indeed, a mythology is needed to be a weapons maker with a bullet, to be able manufacture consent in the wider population over theoretical wars in complex power confrontations, and to sell weapons for companies that employ the people that run our war memorials.

The memory of war is a powerful tool and those who hold it have a responsibility to tend its legacy with respect. In Australia, that legacy has not been one of glory, but primarily one of loss and tragedy. Australia’s war goals have changed, and so has its legacy in the memorial of battle. Conflict of interest in leadership has redefined vital organisations like the AWM and has seen it attached to those who work for companies that foster the promotion of war, instead of preserving its memory.

More than one in two Australians would rather the $500 million war memorial upgrade to be spent on education, health and veterans’ support services instead — a real public interest issue impacting real lives.

We sent thousands of eager young soldiers to their death in the botched landing at Gallipoli. They sung songs for King and country as they departed, and those that returned came home broken to the duress and horror of a post-war nation that was moving away without them. The aftermath of every war fought since has had a comparable story, and it’s a real crisis that is still inadequately addressed today.

The mental health crisis, the avoidable suicides, the self-destruction, and the living sacrifice of veterans in crisis are the real costs. Those with conflicts of interest from the political class, working for transnational weapons companies, should not have a place overseeing the solemn remembrance of war, nor a role defining how we remember those who sacrificed their lives.

Joel Jenkins is a writer and independent political analyst focused on the intersection of class, the state of the nation, and Australian independent policy.