- As a critical and strategic metal, tungsten is central to global development through technology and defence solutions

- China’s dominant position as a tungsten exporter impacts the security of the world’s supply chain

- The world’s largest tungsten deposit in South Korea is the target of a huge reinvigoration project by Almonty Industries (AII)

- Once a significant source of economic activity, Sangdong Mine still has the potential to produce 50 per cent of the world’s tungsten supply, excluding China’s influence

With the unfolding war in Ukraine and disruption of key regions demonstrating the fragility of global trade, there is a simmering urgency for the world to rearm itself ahead of unknown threats in the future.

Eyes have turned to tungsten, a mineral with a volatile supply chain that has played a major role in the development of the modern industrialised world.

Tungsten is a shiny black metal containing small amounts of carbon and oxygen, critical for the manufacture of battery anodes for electrical vehicles, semiconductors, and other green technologies.

With the highest melting point of all metals and usefulness in strengthening alloys, tungsten became a strategic metal during World War II and continues to be an important raw material for the arms industry.

Another useful characteristic of tungsten is that it does not break down or decompose, making it one of the “greenest” raw metals.

Due to the unique properties of tungsten, the metal cannot be substituted in many important applications in different fields of modern technology.

It is not hard to see how tungsten could be critical in the near future.

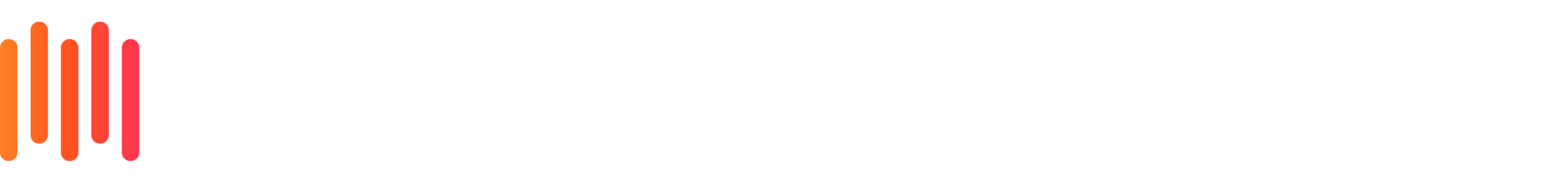

The global demand for tungsten is forecast to grow by between 3 and 7 per cent per year, according to the British Geological Survey and calls are increasing for new sources of strategic minerals like tungsten as supply chain vulnerabilities continue to be exposed during times of regional instability.

But this process may not be so straightforward.

The biggest piece of the pie

As well as controlling 80 per cent of global tungsten production, China enjoys a healthy share of multiple industries across the global trade landscape, including rare earth elements (REE) and resources critical to defence and sustainability initiatives known as strategic minerals.

China dominates the market with 87 per cent of the world’s total REE production, a domination that will only increase with Beijing recently merging three of the state-run “Big Six” rare earth companies — Minmetals Rare Earth, Chinalco Rare Earth & Metals Co and China Southern Rare Earth Group Co — into one.

For a country that already has the biggest piece of the pie in critical industries this is a move that gives China greater influence over the pricing and export volumes as demand is set to increase.

The trade relationship that China navigates with the rest of the world also plays a part in the nation’s continuing dominance, with domestic concerns sometimes tipping the balance of supply and demand with widespread consequences.

This is best illustrated through the urea supply chain crisis that occurred at the end of 2021, leading to a worldwide trade crisis when the production of mandatory urea-based coolants for large vehicles was severely disrupted.

This disruption threatened the viability of trade by freight, and production of urea-based fertilisers was also affected which led to a similar crisis for farmers and price surges for consumers.

International cooperation allowed for exchanges of stockpiled urea and coolants between countries, but such goodwill can never be guaranteed when trade is used as leverage in political disputes.

Although the scales have balanced back in favour of global trade from the production giant, it’s only a matter of time before China shuts the gate again.

One solution to this monopoly is to secure a diversified supply chain for critical minerals such as tungsten.

In the face of such massive consolidation of power and resources, wishing for a diversified supply chain seems unrealistic, but wishes can come true.

The Miracle by Han River

Sharing a border with China, the Korean peninsula could hold the solution to the tungsten supply deficit in a rural community named Sangdong.

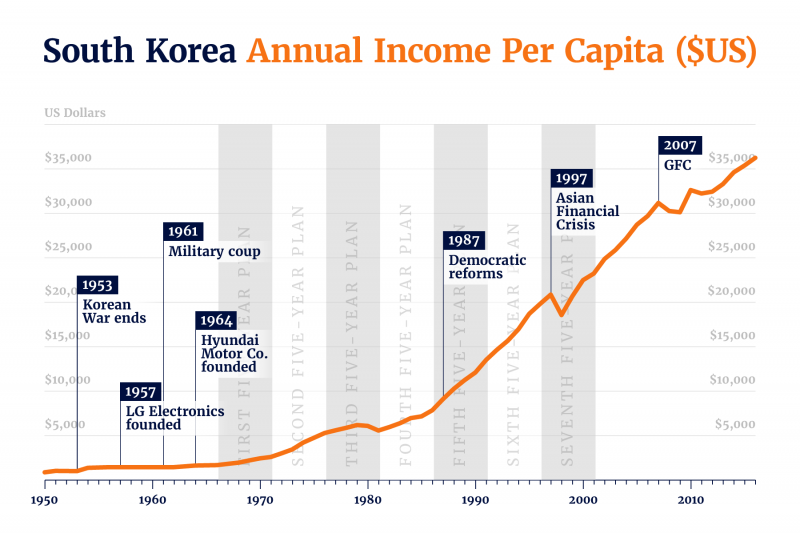

There’s certainly a fairy-tale element to the story of this town and how its economic contribution effectively pulled South Korea out of poverty, transforming the beleaguered nation from one of the poorest countries in the 1960s to the world’s 11th-largest economy.

Known as the Miracle by Han River, the South Korean economic transformation is a dramatic event that lies well within living memory, particularly for the residents of Sangdong.

The town is built to mine, literally.

It is situated next to the largest tungsten deposit in the world, a resource that, until modern technology evolved to its current point and new demands emerged, had a limited scope of application.

However, Korea is now the largest per capita user of tungsten and demand is set to outstrip supply without the development of reliable sources.

The first half of the 21st century was not a period during which industry and development were prioritised in South Korea.

The socio-political events of Korea’s past have fundamentally shaped its economic pathway, particularly in the mining and resources sectors.

A military coup in 1961 established a powerful dictatorship, replacing a previous dependence on aid from the US.

This military government put into motion a series Five-Year Economic and Social Development plans, which systematically expanded the resources industries according to profitability for the nation.

This is the environment in which Sangdong first emerged as an untapped resource of national significance, a jewel in the crown of the government’s plans for economic success.

For Korea, Sangdong represented an emerging economic reality of global demand for a domestic product with the mine contributing more than 50 per cent of the country’s export revenue.

Sangdong’s annual production of tungsten concentrate ranged from 994 metric tonnes in 1955 and 3,268 metric tonnes in 1961 with a total output from 1952 to 1987 topping 74,911 metric tonnes.

The mine was staffed by the residents of the town, a symbiotic relationship that had social benefits beyond the town itself.

Veteran staff from Sangdong recall with fondness the respect afforded to them by the bright orange mining uniform; even on trips to the capital Seoul, the recognition of how Sangdong had contributed to the nation meant that many employees enjoyed free goods and services as a show of gratitude.

The swan song of Sangdong

In the 1990s, the same economic development plans that brought Sangdong to international repute also led to its demise.

The government committed to a focus on technology and electronics, a late-stage capitalist push to replicate the success of its neighbour and former invader, Japan, in the same industries.

Once the beating heart of a country recovering economically and emotionally from war, famine, and military rule, Sangdong was sidelined as manufacturers such as Hyundai, LG, Samsung, and POSCO began to dominate the Korean export market.

The entire mining industry shrank to contribute less than 0.5 per cent of Korea’s GDP, with a widespread perception that the previously fruitful mines had no further resources to offer.

Then tungsten prices dropped in the mid-1980s, forcing the mine to reduce production and eventually shut down in 1992, slipping into hibernation under the hills as residents slowly moved away and moved on.

Those who remained watched as the mine was traded between M&A players, the land banked for later until the next trade was made.

Until one company bought and stayed.

In 2006, a subsidiary of Almonty Industries (AII) secured title of the Sangdong land.

Excluding China’s output, Sangdong – contrary to previously held beliefs – still has the potential to produce 50 per cent of the world’s tungsten supply, providing a viable and secure supply outside of China’s dominant export presence.

With over 125 years of proven results at projects in Spain and Portugal, Almonty is a company rich in the essential mining expertise required to produce tungsten; expertise that is hard to come by these days and is key to reviving the sleeping giant beneath Sangdong.

In preparing the mine for future production, Almonty is also reinvigorating the town with a commitment to economic and community development.

The management team at Almonty Korea were awarded with a plaque of gratitude from the residents of Sangdong:

Your great effort in the developments at Sangdong Village has especially helped our village seniors. With this plaque, we wish to express our deepest gratitude for providing our community at Sangdong Village a better life and great happiness. 30 Nov 2016; Dean of Sangdong Elderly College, Sangho Lee.

The successes and disappointments of the mine at Sangdong form a central part of Korea’s history.

With Almonty at the helm, the town and the tungsten industry could be taken to new heights.

Shares in Almonty Industries remain steady at $1.00 each.

-1280x720-800x430.jpg)

-1280x720.jpg?v=1)