- Australia’s housing market remains a bright spot in an economy grappling with the Delta wave as the RBA keeps the cash rate on hold at record lows

- In seasonally adjusted terms, overall housing credit growth increased by 0.6 per cent in July after a 0.7 per cent increase in June

- The rate of residential mortgages with credit outstanding grew 4.7 per cent, with owner-occupied debt rising 8.7 per cent

- In a survey from Finder, 15 per cent of respondents feared they may not be able to make their repayments once rates creep up

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has decided to keep the cash rate at a record low of 0.1 per cent as the economy reels from the ongoing Delta-induced COVID lockdowns on the eastern seaboard.

Subdued wage and jobs growth, alongside the massive economic impact of continued lockdowns, have led many to predict a looming recession.

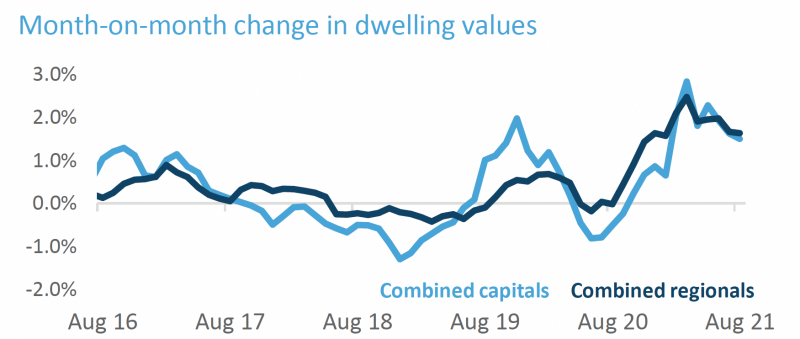

Despite the gloom, Australia’s housing market remains a bright spot.

CoreLogic noted that house prices rose 1.5 per cent in August, resulting in an 18.4 per cent jump from a year ago, or about a $1990 increase per week on average. However wages have grown only 1.7 per cent over the same period, with inflation rising 3.8 per cent.

The ongoing strength in the housing market may raise concerns for the RBA and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), according to CoreLogic research director Tim Lawless, as housing credit growth remains above average and investors comprise a larger component of mortgage demand.

The RBA is looking at trends in housing borrowing to ensure standards are maintained.

“According to the RBA’s private sector credit aggregates, outstanding mortgage debt is rising at the fastest pace since 2010,” Mr Lawless said.

“Since March this year, monthly increases in housing credit growth have remained above the decade average (and) this persistently above-average housing credit growth could trigger tighter credit policies.

“Offsetting this risk is the fact that owner occupiers are continuing to drive the most substantial component of growth in housing related credit. Growth in investor housing credit remains below average and has trended lower over the past two months.”

In seasonally adjusted terms, overall housing credit growth increased by 0.6 per cent in July after a 0.7 per cent increase in June.

Owner-occupied homes led the way, rising 0.9 per cent in a month and adding roughly $1.3 billion to loan books.

Investor housing growth increased by 0.3 per cent, or about $670 million, after a protracted period of stagnation from December 2017 to December 2020.

The percentage of new residential mortgage loans with high debt-to-income ratios rose throughout the June quarter, continuing to be driven by low-interest rates and rising home values, according to APRA’s Quarterly Authorised Deposit-taking Institution (ADI) Performance statistics.

The rate of residential mortgages with credit outstanding grew 4.7 per cent, with owner-occupied debt rising 8.7 per cent.

New residential mortgage loans funded during the quarter ballooned 40.5 per cent year on year, with owner-occupiers taking 70.6 per cent of new mortgage loans, with 27.8 per cent from investors.

Mr Lawless said that while investors were still under-represented in the market, demand could lift above-average credit levels.

“With new credit growth for housing investment substantially outpacing owner occupier lending, investor concentrations could lift to above average levels over coming months, increasing the risk of a regulatory response,” he said.

“In the meantime, as housing values rise more in a month than average household incomes rise in a year, it’s likely that affordability constraints and increased supply will gradually slow buyer activity and price growth across the housing market, with the potential for a sharper slowdown if credit tightening policies or increases to interest rates are implemented.”

According to research from Finder, many homeowners are already worried about affording their mortgage.

In the survey, 53 per cent of homeowners were concerned about interest rates increasing in the near future, with 15 per cent fearing they may not be able to make their repayments once rates creep up.

This ratio rises to 28 per cent for individuals with an annual household income of less than $50,000.

“Low interest rates have encouraged many buyers to purchase earlier than they otherwise might have for fear of missing out,” Finder head of consumer research Graham Cooke said.

“But not all of them will have budgeted for their monthly repayments to go up if or before the cash rate increases.”

Canstar statistics show the average basic owner-occupier principal and interest home loans are on 2.91 per cent variable and 2.25 per cent fixed for a one year term.

In June Westpac increased its two and three-year rates by 0.1 percentage points, while ANZ increased its five-year rate by 0.45 percentage points shortly afterwards.

According to Finder research, the average monthly mortgage payment in Sydney is worth 76 per cent of the average worker’s after-tax wages, making it the most in the country.

Melbourne (57 per cent) is not far behind, with Canberra and Hobart (49 per cent) following closely after. Perth is at the bottom of the list, with an average mortgage costing 35 per cent of typical wages.

Lower-income households that spend more than 30 per cent of their gross income on housing expenditures, which includes rates and mortgage payments, are typically described as experiencing housing stress.

The RBA has said it will likely not increase the cash rate until 2024, but many economists predict it will likely rise in 2022 or 2023.

“Considering the weaker economic conditions and the RBA’s ongoing view that inflation won’t be high enough to trigger a lift in the cash rate until 2024, it’s likely mortgage rates will remain low for an extended period of time, continuing to keep a floor under housing demand,” Mr Lawless said.