- Mortgage stress is on the rise in outer suburban communities and could become a major issue in the upcoming federal election, according to a new analysis

- The data shows that 50 to 70 per cent of renters and mortgagees in key outer suburban locations are in trouble, according to the study

- There are 12 outer suburban areas across Sydney and Melbourne, where more than half the households are now financially stressed

- Investor stress levels varied from 36 per cent to 57 per cent

Mortgage stress is on the rise in outer suburban communities across the country and could become a major issue in the upcoming federal election, according to a new analysis of Digital Finance Analytics survey data.

The data shows that between 50 and 70 per cent of renters and mortgagees in key outer suburban locations are in trouble.

There are 12 outer suburban areas across Sydney and Melbourne where more than half of households are now financially stressed renters and mortgagees, according to the study, with four of these places on the electoral margin.

Households categorised as living within their means have a ‘residual’ income after typical expenditures (including housing costs) of more than five per cent of gross income, households with less than five per cent are classified as stressed in the survey.

The study, which used a random sample of 52,000 homes, also found that the percentage of mortgage holders who were having financial problems increased from 32.9 per cent in February 2020 to 41.7 per cent in July 2021.

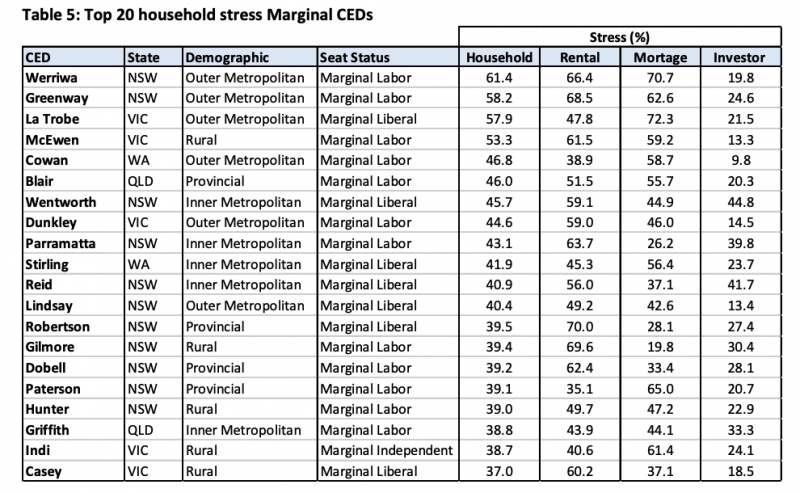

associated renter, mortgagor and Investor stress levels

Household stress in marginal areas ranges from the Liberal seat of Casey (37 per cent) in rural Victoria to the Labor seat of Werriwa (61 per cent) in outer Sydney, with Victoria and NSW making up a significant portion of areas witnessing housing stress.

Investor stress levels varied from 36 per cent to 57 per cent. There were only two constituency electoral divisions outside of the inner city that had the greatest levels of financial stress, but they were spread among five national capitals.

For renters, all but one of the top 20 spots for stress were in NSW and concentrated in urban areas.

New research from UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre, released at the same time as the DFA data study, says Australia’s housing sector needs to be stabilised.

Report lead author Professor Duncan Maclennan said with house prices and mortgage borrowing once again surging in 2021, Australia’s household debt is now at a record national highs.

“It’s especially concerning that all Australia’s major banks have internationally high residential mortgage exposure,” he said.

“That means Australian households and the overall financial system have become highly exposed to interest rate change rates and external economic shocks.

“If the housing market takes a hit from future economic instability, a boost to social and affordable rental would soften the downturn for the entire economy.”

According to the findings of the research, Australia’s household debt will have increased from 70 per cent in 1990 to approximately 185 per cent by 2020, relative to GDP.

Three quarters of the debt is secured by mortgages and 0% of debt held by Australian banks is in the form of residential mortgages.

This level makes it the world’s largest percentage of debt secured by home loans and therefore putting the banking system at risk, the report noted.

A more stable housing market, according to the authors of the paper, would lower the need for macro-prudential lending measures over the long run.

This can be accomplished by advocating for a more active role for the Reserve Bank in housing sector stability management as part of a more focused national government strategy, a role the Reserve Bank has repeatedly denied to undertake.

Report co-author Professor Chris Leishman of the University of South Australia said a growing concern was that authorities were playing hot potato with a housing crisis.

“The Commonwealth Government sees it as something the market will fix, APRA has minimal interest and the Reserve Bank of Australia states that it is outside its remit,” he said.

“Meanwhile, Australian banks and households are gambling everything on the hope of continuously increasing prices.”